Table of Contents

Photo credit: Jamie Lloyd-Taylor & Jungle Press

In this article, I’ll be leaning on my background in English literature and creative writing to take a more poetic approach to Jungle’s new single, “Let’s Go Back.” While the song’s message is pretty direct, I believe it’s a good opportunity to explore some deeper connections through literary history.

By comparing classic poems, we can examine how writers throughout history have dealt with similar emotions—longing, emotional pain, and the desire to revisit the past. These are just my own interpretations, but I hope to offer a fresh perspective on what the song might be communicating on a more universal level.

I find it interesting how music and literature often overlap in exploring human emotion. Poets like Emily Brontë, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning have tackled many of the same themes that come up in “Let’s Go Back”—the frustration of unfulfilled love, the pull to return to a better time, and the emotional weight of separation.

By connecting Jungle’s lyrics to these classic works, my goal is to highlight how timeless these feelings really are, and how modern songs like this one can still speak to those age-old struggles.

Visit here for tickets and see the full list of Jungle’s Tour dates.

SEPTEMBER

10 – Cardiff, Utilita Arena

12 – London, The O2

13 – Belfast, Custom House Square

14 – Manchester, Depot Mayfield

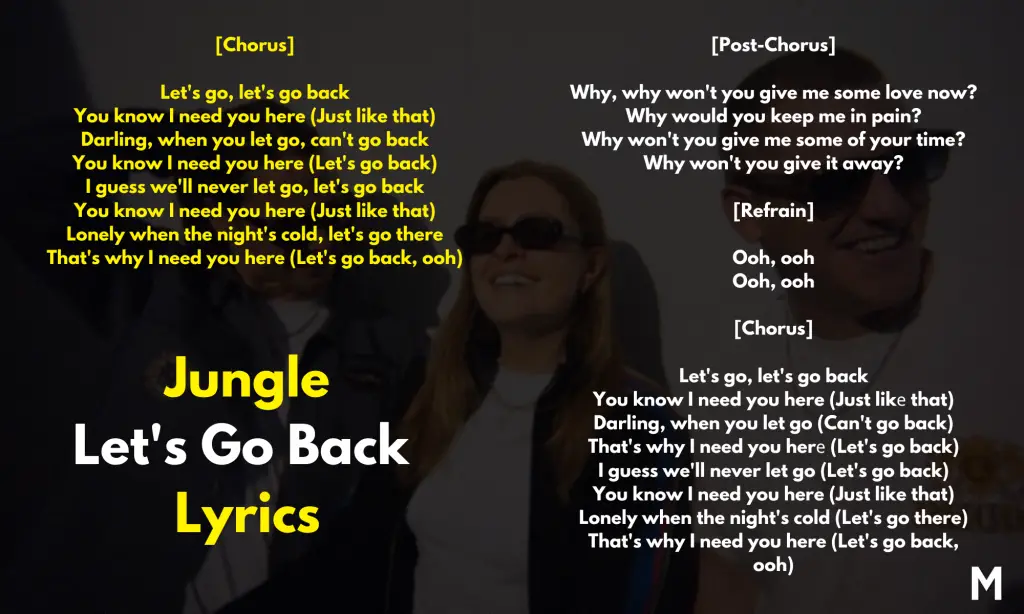

Jungle Let’s Go Back Lyrics:

Jungle Let’s Go Back Meaning:

ntroduction: Establishing the Emotional Framework

The song’s lyrics center on a familiar emotional landscape—the desire to recapture a past relationship and the overwhelming pain of emotional neglect. From the opening plea, “Let’s go, let’s go back,” the speaker establishes a deep longing to return to a time when things felt more stable and loving. Throughout the song, the speaker repeatedly expresses their desperation for connection, building on the idea of emotional dependency.

This theme of yearning to restore something that has been lost is mirrored in Emily Brontë’s Remembrance, where the speaker reflects on a lost love: “Cold in the earth—and fifteen wild Decembers / From those brown hills have melted into spring.” Brontë’s speaker acknowledges the passage of time, but like the song’s speaker, they remain emotionally tethered to the memory of what once was. Both pieces explore the tension between the inevitability of moving forward and the inability to emotionally let go of the past.

In the song, the lines “Darling, when you let go, can’t go back” capture this internal conflict perfectly—the speaker knows they cannot truly return to the past, yet the emotional urge to do so remains.

Close Reading of the Chorus: Longing and Emotional Dependency

In the Chorus, the speaker’s yearning becomes more explicit:

- “Let’s go, let’s go back / You know I need you here (Just like that)”

This repetition of “let’s go back” signifies the speaker’s desperation to return to an idealized moment of emotional connection. The use of the word “need” highlights the intensity of the speaker’s feelings—it’s not just a desire, but an emotional necessity. I believe this underscores the theme of emotional dependency, which we see echoed in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 29. In the sonnet, Browning’s speaker describes a similar sense of longing for a distant lover: “I think of thee!—my thoughts do twine and bud / About thee, as wild vines, about a tree.”

Much like the speaker in the song, Browning’s speaker cannot help but feel incomplete without the presence of their beloved. Both works suggest that the speakers’ emotional well-being is tied to the closeness of another person, and without that, they feel unmoored.

- “Lonely when the night’s cold, let’s go there”

This line introduces imagery of isolation, suggesting that the speaker feels emotionally abandoned. The night, often symbolic of vulnerability and fear, paired with the cold, emphasizes the speaker’s loneliness. In Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind, we see a different but related kind of longing for change and renewal: “O Wind, / If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?” Shelley’s speaker yearns for the transformative power of the wind, much like the speaker in the song yearns for the other person to bring emotional warmth back into their life.

Both pieces highlight the desperation that comes with emotional stagnation—the feeling that without some kind of reconnection or renewal, the speaker will continue to feel adrift.

Post-Chorus: Frustration and Emotional Rejection

In the Post-Chorus, the lyrics take a more direct turn toward frustration:

- “Why, why won’t you give me some love now? / Why would you keep me in pain?”

Here, the speaker is no longer just pleading for connection—they’re questioning why it’s being withheld. This shift from yearning to frustration is key to understanding the depth of emotional pain the speaker feels. They aren’t just missing the other person; they feel actively rejected, wondering why their need for love is being ignored. Browning’s Sonnet 29 again comes to mind, where the speaker imagines the return of their beloved as a way to ease their internal anguish.

“I do not think of thee—I am too near thee,” Browning writes, suggesting that the mere presence of the beloved would dissolve the speaker’s emotional turmoil. Similarly, the speaker in the song believes that if only they could have some of the other person’s love, their pain would be alleviated.

- “Why won’t you give me some of your time? / Why won’t you give it away?”

These lines highlight the speaker’s sense of imbalance in the relationship. Time and attention—seemingly simple things—are withheld, leaving the speaker confused and hurt. The repetition of these questions reinforces their desperation and confusion. This imbalance is also present in Brontë’s Remembrance, where the speaker laments the loss of a connection that time and distance have made impossible to restore: “Faithful, indeed, is the spirit that remembers / After such years of change and suffering!”

Brontë’s speaker, much like the one in the song, feels the weight of unreciprocated emotion and the ongoing struggle to reconcile their longing with the reality of the other person’s absence.

Refrain and Outro: Wordless Expression of Pain

The Refrain and Outro consist of repeated vocalizations:

- “Ooh, ooh”

This wordless refrain suggests that the speaker has reached a point where words are no longer enough to express their emotional state. It’s a moment of surrender—after all the pleading and questioning, the speaker is left with nothing but their pain. In Ode to the West Wind, Shelley’s speaker also reaches a moment of resignation, recognizing that while they yearn for transformation, they are at the mercy of forces beyond their control: “Make me thy Lyre, even as the forest is.”

This sense of powerlessness is echoed in the song’s refrain—the speaker can no longer verbalize their pain, because the emotional burden has become too great for words.

Themes, Meanings, and Main Takeaways

The song’s lyrics, like the works of Brontë, Shelley, and Browning, delve into the deep emotional pain of longing for reconnection and the frustration of unfulfilled desires.

At the heart of the song is a desire to restore a lost relationship, but also a growing awareness that this may not be possible. The repeated line “let’s go back” reflects the speaker’s emotional impulse to return to a time when things felt more secure. This theme of yearning to return to the past is similarly explored in Brontë’s Remembrance, where the speaker is haunted by memories of a lost love, and yet acknowledges that they cannot fully return to what once was. Both the song and Brontë’s poem grapple with the painful reality of time and emotional separation.

Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind brings in another layer to the song’s themes—the desire for renewal and transformation. The speaker of the song doesn’t just want to go back in time; they want to revive the emotional warmth that has been lost. Shelley’s speaker, too, seeks change, calling upon the wind to renew and revitalize them. Both works reflect the emotional powerlessness that comes with longing for change that feels beyond one’s control. In both the song and Shelley’s poem, the speakers recognize their limitations and the pain that comes with feeling emotionally stuck.

Finally, Browning’s Sonnet 29 deepens the theme of emotional dependency. The song’s speaker repeatedly pleads for time and attention from the other person, feeling incomplete without it. Browning’s speaker similarly longs for the presence of their absent lover, imagining their return as a way to soothe their emotional turmoil. Both works illustrate how deeply intertwined emotional well-being can be with the presence of a loved one, and how painful it can be when that connection is missing.

The main takeaway from both the song and these poems is the complexity of longing, memory, and emotional pain. Each speaker is caught in a cycle of yearning for something lost, and the frustration of knowing that, in some ways, it may never be fully restored.

The post Jungle Let’s Go Back Lyrics And Meaning: Connecting Modern Music to Classic Poetry appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.