Table of Contents

Image Credit To MCA Records Inc. For Commentary and Educational Purposes.

It’s funny how Learning to Fly ended up being one of Tom Petty’s most enduring songs, considering he wrote it during a stretch where things weren’t exactly taking off. The band had just wrapped Full Moon Fever, and sure, he’d scored hits like Free Fallin’ and I Won’t Back Down, but there was this weird hollowness around it. Jeff Lynne was still hanging around the studio for Into the Great Wide Open, but Petty was chewing on heavier stuff—frustrations, changes, people falling away.

And the world wasn’t helping either. There was a war on the TV. He kept seeing footage of oil fields burning and landscapes swallowing themselves.

Somewhere in all that noise and smoke, Petty hears a pilot say something that sticks: “Flying’s easy. Landing’s hard.” That’s the line that breaks the seal. He runs with it, but doesn’t dress it up. Doesn’t turn it into a sermon. Just builds a melody around it and lets the truth sit there, quiet but firm. And maybe because of that, the song hits differently than some of the flashier tracks from that era.

And even though it never hit No. 1, it became the kind of song people bring with them—through moves, deaths, breakups, reinventions. That kind of song doesn’t care about charts.

So this is me taking a closer look at it—not to make it mean more than it does, but to show what might be hiding just under the surface. I come at it as someone who’s read a lot of poems, written a few myself, taught some literature classes, sat with lines way longer than I probably should. This is not me saying I know what it all means. Just trying to pull on the threads a little and see where they lead.

And I’ll be honest: I also just wanted a good excuse to compare this song to the kinds of things I’ve found buried in old poems and quiet novels. That’s the lens here. Nothing more mystical than that.

Learning to Fly, at a glance

- Started as a lyric pulled from a real-life pilot’s offhand comment and ended up becoming one of Petty’s most steady-burning tracks.

- Wrote it with Jeff Lynne during a rough patch—divorce, band tension, world on fire (literally)—but the song walks with light feet.

- Not a chart-topper, but it stayed. The kind of song that shows up when life gets uncertain and you need something that knows how that feels.

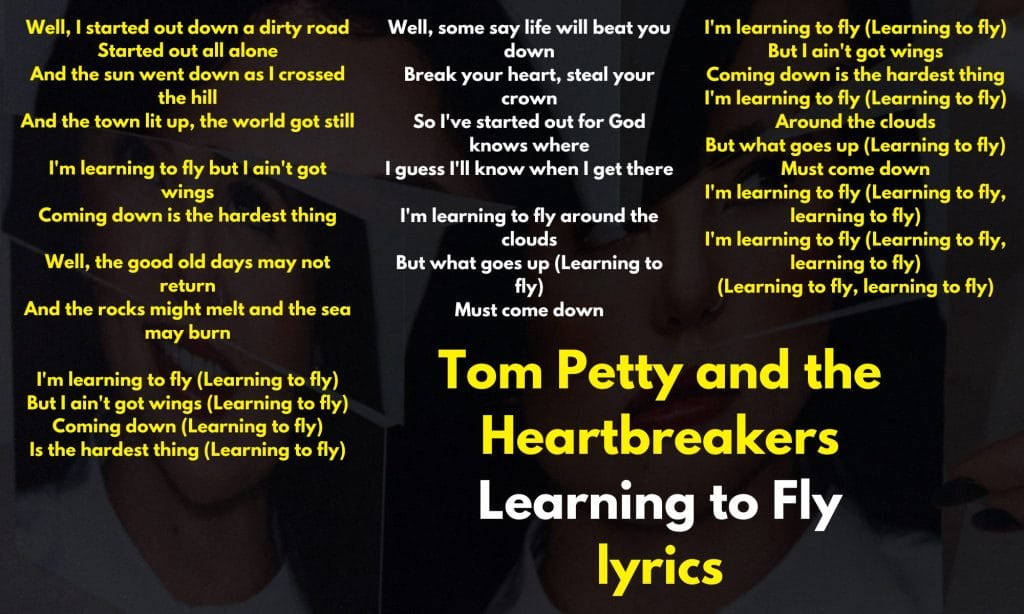

Lyrics

Learning to Fly Meaning

Well, I started out down a dirty road / Started out all alone

This is how most true journeys begin. No promise of glory. No parade. Just someone putting one foot in front of the other, not because they know where they’re going, but because staying still no longer feels like an option. A “dirty road” is not metaphorical—it’s literal, and it sets the tone. Messy, unclear, real.

W.S. Merwin once wrote:

“You will never have heard a sound like this before…”

That’s how the start of something unknown feels. Strange, quiet, and unfamiliar. The speaker here is alone, and not by choice. But there’s no fear in the line. Just fact. Starting is never clean. And being alone is part of learning what forward even means.

Tom Petty said this song came out of a hard stretch—tensions in his band, divorce, and the world looking bleak. He wanted the words to reflect something steady, something lived-in. Not triumph. Not tragedy. Just motion. That first step matters more than people think.

I’m learning to fly, but I ain’t got wings / Coming down is the hardest thing

Here is the line that holds everything. Trying to grow, to change, to rise—even without the tools that usually make those things possible. No wings means no cushion. And still, flight is happening. That’s the tension.

Philip Larkin, in his poem Aubade, offers this:

“Most things may never happen: this one will.”

He’s talking about death. But he’s also talking about certainty. Larkin doesn’t bother with comfort—he stays rooted in the fact that some falls are coming, no matter how high you’ve flown. Petty knows that truth, too. That “coming down” line doesn’t whine. It accepts. It owns the cost of trying.

Tom once said a pilot gave him the line. The guy told him flying was easy—landing was the hard part. That stuck with him. Not just as a clever metaphor, but as something bigger. Like everything: learning how to live takes more out of you than people admit.

The good old days may not return / And the rocks might melt and the sea may burn

Now we’re walking through the ash. Petty is not looking back with rose-colored glasses. The past is gone. The future might be worse. These are lines built out of wreckage. Gulf War images played in the background when he wrote them. He saw oil fields on fire and coastlines glowing with heat. That found its way into the song.

Louise Glück, in The Wild Iris, writes:

“Whatever / returns from oblivion returns / to find a voice.”

Destruction happens. But voice can return. Even when everything looks scorched. That’s what this verse leans toward—not hope, not despair, but endurance. If the sea burns and the rocks melt, then what matters is whether or not you keep walking through it.

There’s nothing heroic in these lines. No pitch for nostalgia or fake confidence. Just someone reckoning with change and decay, and still speaking.

Some say life will beat you down / Break your heart, steal your crown

This verse moves close to the bone. Petty lays it out: you can try, and life will still hit you. It will take from you—your joy, your place, the things you thought were yours to hold. A crown doesn’t mean royalty here. It means something you earned, maybe even just peace. And losing it? That hits hard.

Still, he sings:

“I’ve started out for God-knows-where / I guess I’ll know when I get there.”

That line, in all its openness, carries strength. Not from knowing. From going. From choosing motion when standing still might feel safer. Glück’s voice echoes here again—this idea that something rises up from nothing and finds a way to speak again.

Petty’s not offering answers. He is walking with the questions, and that’s more useful anyway. Nobody who’s been hit wants advice. They want someone who’s been there and still moving.

I’m learning to fly around the clouds / But what goes up must come down

This is where the song lifts and falls at the same time. Clouds mean height. Clouds mean escape. But gravity is coming. Always. That truth rings out again and again. Not to scare the listener, but to keep them honest.

Petty didn’t mean this to sound like hope in the usual way. He meant it to feel like a hand on your shoulder. Something quiet, sturdy, and unshakable. The world throws hard things your way. You might rise. You might crash. But you learn. And sometimes that’s what matters most.

The poets we’ve looked at—Merwin, Larkin, Glück—they all write in this space. Between trying and failing. Between rising and falling. Between silence and voice. What Petty does here with guitar and a few words, they do with lines built to last.

Connecting All The Dots For Me

If there’s a thread running through Learning to Fly, it’s the quiet admission that personal growth does not come with instructions—or safety features. Petty wasn’t in a moment of triumph when he wrote this. He was navigating a messy divorce, his band was shifting under his feet, and the Gulf War was flickering in the background of his daily life. “The rocks might melt and the sea may burn” is not a metaphor you reach for unless you’ve been staring at footage of oil fires for too long. That kind of writing comes from pressure.

It’s the same kind of pressure Merwin moves through in The Nomad Flute, where every step forward happens in a space stripped of certainty. You don’t know where you’re going. You go anyway.

The refrain—“I’m learning to fly, but I ain’t got wings”—does not offer progress as anything clean. It recognizes the ache that comes with forward motion. Larkin’s Aubade is a more brutal mirror to that sentiment: “Most things may never happen: this one will.” He’s talking about death, sure, but he’s also talking about inevitability. The fall is always baked into the rise. Petty never tries to dodge that. He accepts it.

That chorus doesn’t reach for the heavens—it just looks up, acknowledges gravity, and still lifts off. That’s the song’s backbone: not hope, exactly, but resolve. Not overcoming, just continuing.

Then Glück’s voice shows up in the song’s softer shadows. In The Wild Iris, she writes, “Whatever / returns from oblivion returns / to find a voice.” That’s what Petty is doing too. He’s writing not from the peak of success, but from the slow return—the quiet recovery after life has knocked everything out of order. There’s no fixed direction in these lyrics, just a willingness to begin again. “I’ve started out for God-knows-where / I guess I’ll know when I get there” says it all. The power of Learning to Fly comes from how gently it holds the truth that motion is survival. The direction matters less than the decision to move.

These aren’t the words of a man reaching the summit. They’re the words of someone finding enough breath to keep going.

The post Learning to Fly Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers Meaning: No Wings, No Map, Just Motion appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.