If you’ve spent any time in Berlin’s underground, you’ve probably brushed up against something iorie touched—whether you realized it or not. With a catalog that spans Watergate Records, Hoomidaas, Akumandra, and his longtime home Kater Blau, the German producer has helped define the character of downtempo and slow house since the genre’s earliest days.

His signature sound blends low-slung rhythms with melodic vocals and off-kilter textures, often anchored by an emotional throughline that stays with you long after the song ends.

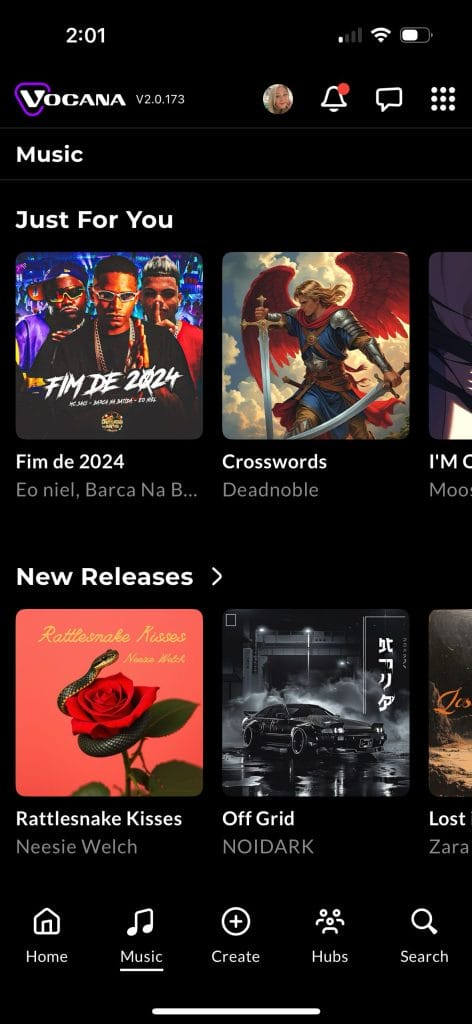

This year, iorie’s output has been especially active, landing collaborations with Gorje Hewek, Alexey Union, and Marius Drescher, as well as solo efforts like “Italian Devine” and upcoming releases this year with Sydka and Luca Musto and another upcoming EP on Hoomidas.

But it’s not just the releases—it’s the way he thinks about arrangement, editing, and creative trust that makes his workflow so compelling.

In this interview, iorie gets into how he separates strong ideas from distractions, how he stress-tests early sketches, and why his best songs often start outside the studio. He also opens up about remix pressure, burnout, and how to stay out of “reiteration hell”—his term for the spiral that happens when you second-guess your ideas into oblivion.

How do you know an idea has enough in it to carry a whole track?

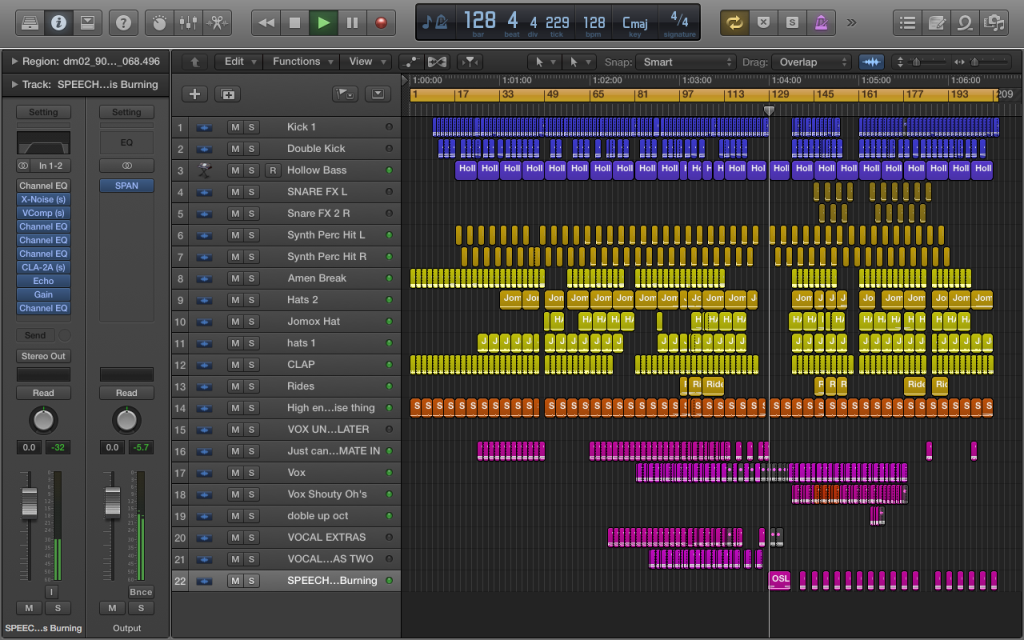

It’s not always easy to tell. I usually start with a loop—something simple like kick, bass, chords, clap, percussion, and shakers. If that already feels like it can hold a moment, I know there’s potential for arrangement.

Sometimes it’s about the variation I’ve built into the sounds themselves—maybe the synths can rise and fall, or the rhythm has multiple versions, or the vocal has a few different phrases.

You can feel pretty quickly if something’s cool, but whether it can carry an entire track comes down to those deeper layers.

When do you test structure, and when do you trust feeling?

I start with a loop, so structure doesn’t really exist yet. That idea often comes to me outside the studio—on AirPods, laptop speakers, wherever. I love those moments because it’s all about feeling. No technical questions. No wondering if it sounds “right.” I’m just chasing a vibe in real time.

Structure comes later. Once I’m in the studio, I shift into engineer mode and try to make that initial sketch work on any system. I actually prefer to build structure in one go rather than keep reworking it.

If I redo it too many times, it feels like a chore, and I lose the energy that made the sketch exciting in the first place.

Have you ever forced a weak idea to completion and regretted it?

I’ve definitely spent too long on ideas I should’ve let go. But most of the time, if it doesn’t click, it never makes it to the finish line. That way I only lose a little bit of time.

Sometimes those unfinished ideas still have value—I go back later, bounce out the best parts, and put them in my personal sample library. They often find a second life that way.

The only real regret comes with paid remixes. That’s where I’ve pushed through weaker ideas just because I felt like I had to deliver.

I try to avoid that now—it’s one of the reasons I’m not a big fan of remixing for money. It doesn’t lead to good creative decisions.

Do you ever build around one core idea only?

Depends on the track.

For club-focused work, I usually have a core groove that carries the energy with slight variations. But if I’m making something more musical, I like to bring in totally new ideas for the B section. I love when a track switches directions in the second half—it adds surprise and depth.

It’s a little frustrating that so many electronic tracks have become shorter, like pop songs.

There’s less space for those kind of explorations, and that’s where the uniqueness often comes from.

What’s your process for stress-testing early sketches?

The first test is how much I want to listen to it the next day. If I play it 10 or 15 times in a row, that’s a good sign. If I only play it once or twice, it’s probably not there yet. That’s my personal metric—and it usually lines up with how others respond.

As a mastering engineer, I can also gauge pretty quickly if the mix is solid. But nothing replaces the club test. The real question is: do I want to play it myself? And then, does the emotion translate in the room?

I don’t fully trust the sound system, but I trust the vibe. If it feels good on the floor, that’s what matters.

How do you protect good ideas from getting diluted?

I try to work fast and make quick decisions. Changing things later rarely makes them better—it just makes them different. And when you change something, it usually affects everything else. Then you’re stuck reworking later parts, and it pulls you away from what the track was in the first place.

So I prefer to finish the track, accept it for what it is, and move on. That keeps me out of what I call “reiteration hell.”

How do you know when to expand vs. when to cut?

For me, cutting is usually the better move. I tend to over-layer, so I’ll mute parts to see what still works. If a track feels too busy or nervous, that’s my sign to simplify. It’s easier to hear that after stepping away for a bit.

Sometimes the arrangement itself feels rushed—that’s when I know I need to expand a section and let it breathe. But if the track feels thin or repetitive, I’ll add elements or cut the structure to keep it interesting.

It’s all about feel. Am I listening to something that moves, or something that’s stuck?

The post How iorie Builds Tracks That Last—and Knows When to Walk Away appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.