Table of Contents

Images C/O Rimas Entertainment LLC

Bad Bunny’s “NUEVAYoL” is inspired by the salsa classic “Un Verano en Nueva York” by Andy Montañez, this track blends reggaetón and salsa into a modern anthem about Puerto Rican pride, life in New York City, and the complex feelings of connection and nostalgia that come with living away from home. The song recently took the spotlight during a surprise performance in the New York subway, where Bad Bunny, disguised with Jimmy Fallon, delighted commuters in an impromptu concert that quickly went viral.

The track is part of Bad Bunny’s latest album, Debí Tirar Más Fotos, which has been topping charts since its release. The album itself is a love letter to Puerto Rican culture, exploring themes of migration, gentrification, and the shared experience of the diaspora. But “NUEVAYoL” stands out because it’s both a celebration of summer in the Big Apple alongside a deeper reflection on identity, heritage, and the challenges of balancing pride in one’s roots with the realities of living in a global city like New York.

In this article, I’ll use my background in English literature and creative writing to explore the lyrics of “NUEVAYoL” more poetically. These are just my own takeaways, but I hope to add some nuance to the conversation.

NUEVAYoL at a Glance

- Cultural Pride: This song celebrates Puerto Rican identity and legacy, weaving in references to icons like Willie Colón and spaces like Toñita’s bar in NYC.

- Urban Energy: “NUEVAYoL” captures the charm and chaos of New York summers while nodding to the complex realities of migration and gentrification.

- Timeless Themes: NUEVAYoL blends the joy of living in the moment with reflections on heritage and connection.

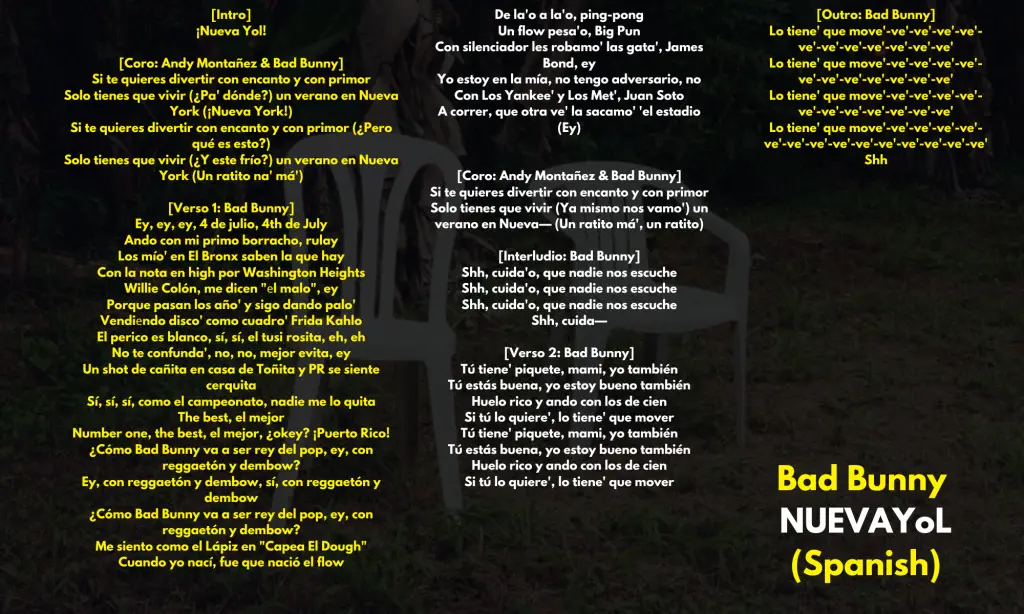

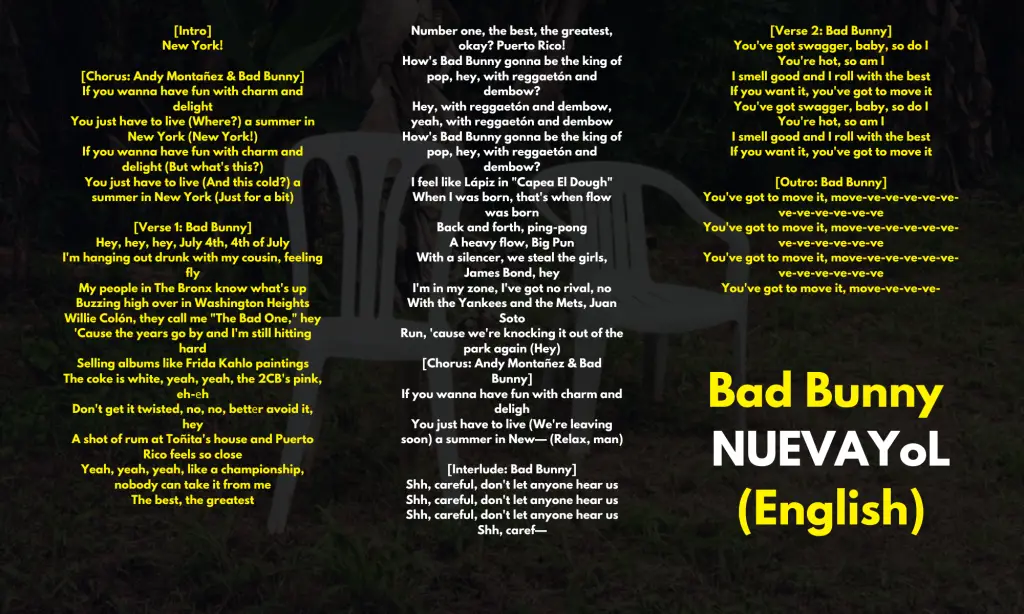

Bad Bunny NUEVAYoL Lyrics (English & Spanish)

Bad Bunny NUEVAYoL Meaning

“A shot of rum at Toñita’s house and Puerto Rico feels so close”

Bad Bunny uses this line to show how, even in a bustling city like New York, he holds onto his Puerto Rican identity. Toñita’s is more than just a bar—it’s a symbol of connection. For many Puerto Ricans in New York, places like Toñita’s are safe havens where culture, food, music, and memories come alive. When Bad Bunny mentions it, he’s showing us how cultural spaces in the diaspora help people stay close to their roots.

This idea ties directly to Pedro Pietri’s “Puerto Rican Obituary,” where the poet writes about Puerto Ricans navigating life in New York while preserving their cultural identity. Pietri describes Puerto Rican immigrants who work tirelessly but dream of returning home:

“Juan / Miguel / Milagros / Olga / Manuel / All died yesterday / dreaming about tomorrow.”

Like the people in Pietri’s poem, Bad Bunny’s rum at Toñita’s is more than just a drink—it’s a way to feel connected to the place he came from, even in a foreign space.

To me, this shows how important it is to have cultural landmarks in a big city like New York. Without them, it’s easy to feel lost or disconnected. Bad Bunny reminds us that no matter where you go, your culture stays with you through the people, places, and traditions you hold close.

“Hey, hey, hey, July 4th, 4th of July / I’m hanging out drunk with my cousin, feeling fly”

Here, Bad Bunny brings us straight into a vivid summer moment. It’s a simple line, but it’s packed with energy and familiarity—spending time with family, celebrating a holiday, and soaking up the vibe of the city. The Fourth of July is a uniquely American holiday, but for Bad Bunny, it becomes a moment where Puerto Rican culture and American culture mix.

Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died” has a similar focus on small, personal moments in a big city. O’Hara describes an ordinary day, but it’s filled with specific details that make it feel alive, like when he writes:

“I walk up the muggy street beginning to sun / and have a hamburger and a malted and buy an ugly NEW WORLD WRITING to see what the poets in Ghana are doing these days.

Both O’Hara and Bad Bunny capture how everyday moments in a city can feel special. For Bad Bunny, it’s a night with his cousin; for O’Hara, it’s grabbing a hamburger and walking through the city.

What stands out here is the mix of joy and nostalgia. Bad Bunny’s cousin makes him feel at home in a foreign space, just as O’Hara’s small details remind him of something bigger. Both show us that even in a big city, it’s the little, personal moments that stick with you.

“The coke is white, yeah, yeah, the 2CB’s pink, eh-eh / Don’t get it twisted, no, no, better avoid it”

This line gives us a glimpse of the wilder side of New York. Bad Bunny is describing a party scene full of temptation and excess, but he also adds a warning: “better avoid it.” He’s not just glorifying the lifestyle—he’s showing us that it comes with risks.

This makes me think of Martín Espada’s “Alabanza: In Praise of Local 100,“ which honors the restaurant workers who died in the World Trade Center during 9/11. While the poem is about a tragic event, it also highlights the joy and resilience of these workers. Espada writes:

“Alabanza to the cook who seasoned his dishes with garlic and thyme and the grin of his grandmother flashing across his soul.”

Both Espada and Bad Bunny show how life in the city is full of contrasts—joy and danger, celebration and caution. For Bad Bunny, the white and pink drugs represent the allure of the nightlife, but his caution shows that he’s aware of the darker side, just as Espada honors the beauty of the workers’ lives while mourning their loss.

By including this warning, Bad Bunny reminds us that not everything in the city is glamorous. It’s a layered message: enjoy yourself, but don’t lose sight of what really matters.

“Shh, careful, don’t let anyone hear us”

This line stands out because it’s so different from the rest of the song. It’s quiet and intimate, almost like Bad Bunny is stepping away from the party for a moment to share something personal. In a song that’s mostly about celebration, this line shows us another side of him—more private and vulnerable.

Frank O’Hara does something similar in “The Day Lady Died.“ Most of the poem is about an ordinary day, but then it shifts to a deeply emotional memory of Billie Holiday singing:

“while she whispered a song along the keyboard to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing.”

Like O’Hara, Bad Bunny uses a sudden shift in tone to catch the listener off guard. It’s a reminder that even in moments of joy, there’s always something deeper happening beneath the surface.

For me, this line highlights the duality of life in a big city. On the outside, everything seems loud and exciting, but on the inside, people have their own quiet struggles and thoughts. Bad Bunny’s whisper feels like a pause in the chaos, a moment to reflect on what’s really important.

“Move-ve-ve-ve-ve-ve-ve-ve”

The song ends with this playful, rhythmic outro, bringing the energy back up after the quieter interlude. It’s a perfect way to close things out—fun, catchy, and full of life. But when you look at the whole song, you realize it’s about more than just dancing.

Bad Bunny has taken us on a journey through New York, showing us the city’s energy, its temptations, and its connections to Puerto Rican culture. By ending on this note, he’s reminding us to celebrate life, even with all its ups and downs.

This celebratory ending ties back to Pedro Pietri’s “Puerto Rican Obituary,” where he writes about dreaming of a better tomorrow. Pietri’s poem ends on a hopeful note, just like Bad Bunny’s song, showing us that no matter how hard life gets, there’s always room to dream, dance, and move forward.

Connecting All Of The Dots here

Bad Bunny’s “NUEVAYoL” uses vivid imagery and cultural references to reflect on identity, migration, and the complexities of urban life. Lines like “A shot of rum at Toñita’s house and Puerto Rico feels so close” show how spaces like the Caribbean Social Club in Brooklyn serve as a bridge between Puerto Rican heritage and life in New York. These lyrics capture the feeling of holding onto your roots in a city that’s constantly in motion, echoing the experiences of many in the Puerto Rican diaspora.

This idea ties directly to Pedro Pietri’s “Puerto Rican Obituary.” Pietri’s poem reflects on the struggles of Puerto Ricans working and living in New York while fighting to maintain their identity. In one striking line, Pietri writes, “They worked ten days a week and were only paid for five,” illustrating the relentless grind of city life. Bad Bunny’s lyrics carry this same tension. The celebration at Toñita’s offers a reprieve from the challenges of living in a space that can feel unwelcoming, yet it also speaks to the strength of a community that refuses to let its culture be erased.

The song also connects with Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died” and Martín Espada’s “Alabanza.” O’Hara’s attention to small, everyday moments in the city parallels Bad Bunny’s line “July 4th, 4th of July / I’m hanging out drunk with my cousin, feeling fly.” Both pieces find beauty in fleeting snapshots of urban life. Meanwhile, Espada’s “Alabanza” celebrates the resilience of working-class Latinos in New York, acknowledging both their struggles and their cultural contributions. That same duality runs through “NUEVAYoL”—a song that is as much about the joy of connection as it is about the challenges of holding onto those connections in a rapidly changing world.

The post Bad Bunny NUEVAYoL Lyrics and Meaning: Heritage and Hedonism Explored appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.