Table of Contents

Images Credit To Daughters of Cain Records

Ethel Cain’s “Pulldrone” feels like a bold turning point—not just in her music, but in the way she tells stories. It’s a 15-minute descent through emotional and spiritual chaos, structured as twelve numbered sections that play like a dark, unsettling liturgy.

Taken from her sophomore release, Perverts, this track pushes even her most loyal fans into unfamiliar territory, leaning heavily on ambient drone and abstract storytelling.

If you’re coming to this from the Southern Gothic melodrama of Preacher’s Daughter, you might find yourself caught off guard by how stark and experimental this song is. But in true Ethel Cain fashion, there’s a payoff here if you’re willing to sit with it.

The song’s heavy spiritual themes—apathy, resentment, divine longing—are steeped in Cain’s Southern Baptist upbringing, a recurring thread throughout her music. “Pulldrone” echoes many of the same obsessions: cycles of suffering, forbidden knowledge, and an almost mythic fall from grace.

If Preacher’s Daughter conjured images of backwoods churches and family trauma, Pulldrone (and accompanying album Perverts, of which is the 6th track) feels more existential, like staring into the void and trying to pull meaning from its depths. With my background in literature and creative writing, I see this as a chance to stretch some literary comparisons and explore how Cain’s storytelling connects to bigger themes in myth, history, and modern fiction.

These are just my takeaways, but I think digging deeper into these lyrics can offer us a clearer view of what makes this song, and Cain’s work as a whole, so timeless and challenging.

Pulldrone Ethel Cain Meaning And Lyrics at a Glance

- A Descent Into Spiritual and Emotional Chaos: The song’s twelve numbered sections read like a modern liturgy, charting a journey through apathy, longing, resentment, and annihilation.

- Mythological and Existential Themes: References to fallen angels, forbidden knowledge, and cycles of suffering create a narrative steeped in symbolism.

- A Structure That Challenges and Rewards: At over 15 minutes long, “Pulldrone” is dense and uncompromising, but its layered storytelling offers plenty to unpack for listeners who stick with it.

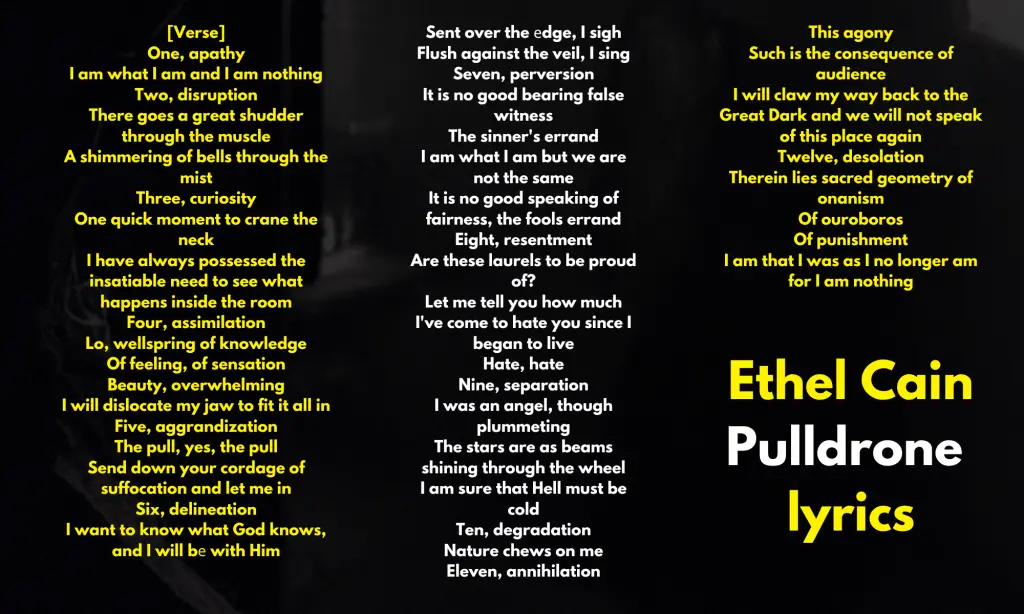

Pulldrone Lyrics

Pulldrone Meaning

“I am what I am and I am nothing”

The opening line is striking in its simplicity and weight. The narrator claims an identity but then immediately negates it, saying they are “nothing.” This contradiction feels deliberate, setting up a theme of existential emptiness. It’s a bold way to begin, almost as if the narrator is saying, “I exist, but I don’t matter.” This idea of being stuck in a void reminds me of Tomas Tranströmer’s Tracks, where he writes, “We grow still, we are led slowly forward.” Both the song and the poem capture that feeling of existing in a state of emptiness, unable to move forward with purpose.

What’s powerful here is how the song doesn’t sugarcoat this apathy. The narrator admits they feel like nothing, which is something many of us might be afraid to say out loud. It’s an honest place to start the journey. By doing this, the lyrics set the stage for the transformation that follows, as if they’re saying, “This is where I begin. Let’s see where it takes me.”

This nihilism also ties into a bigger question about the meaning of life. Are we just here to exist, or is there something more? The narrator doesn’t seem to have the answer yet, but this line feels like the first step toward finding out—or at least trying to.

“A great shudder through the muscle”

This line signals a change, a moment where something inside the narrator shifts. The “shudder” feels like a wake-up call, a physical reaction to an emotional or spiritual disruption. It’s as if the narrator is being forced out of their apathy, even though they might not want to be. The imagery of “a shimmering of bells through the mist” adds a mystical, almost spiritual quality to this moment. It reminds me of Anne Carson’s The Glass Essay, where she writes, “The pain entered like a piece of glass.” Both the song and the poem use physical sensations to show how emotional or spiritual awakenings can feel raw and unsettling.

What I love about this section is how it connects the body and the mind. The narrator isn’t just thinking about this change—they’re feeling it in their muscles, in their very being. This makes the disruption feel real and unavoidable. The bells in the mist also add a sense of mystery, like something bigger than the narrator is at play here.

This moment is important because it shows that even when we try to stay stuck in apathy, life has a way of shaking us up. The narrator can’t ignore this shudder, and that sets the tone for the rest of the journey.

“One quick moment to crane the neck”

Curiosity takes over here. The narrator’s desire “to see what happens inside the room” feels almost primal, like they can’t help but look. This need to know what’s beyond the door ties into the human thirst for understanding. It’s that same hunger for knowledge that we see in Rilke’s The Second Elegy, where he writes, “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic orders?” Both the song and the poem capture how curiosity drives us to ask big questions, even when we know the answers might be painful.

This line also feels deeply relatable. We’ve all had moments where we just had to know what was behind a door, even if it scared us. That’s what makes this part of the song so human. The narrator isn’t just curious—they’re insatiably curious, which hints that this drive for knowledge might take them places they’re not ready for.

In a way, this moment feels like the narrator’s first real choice. They could stay where they are, but instead, they crane their neck to see what’s ahead. It’s a small action, but it has big consequences.

“I will dislocate my jaw to fit it all in”

This is one of the most intense lines in the song. The narrator tries to take in everything—beauty, knowledge, feelings—but it’s too much. The image of “dislocating my jaw” is vivid and unsettling, showing how far they’re willing to go to consume it all. It’s almost painful to imagine. This desperation reminds me of Anne Carson’s The Glass Essay, where she writes, “Desire doubled by knowledge, what a cruel thing.” Both the song and the poem show how overwhelming it can be to try to take in more than we can handle.

What makes this line stand out is the sheer force of the narrator’s hunger. They’re not just curious anymore—they’re desperate, even self-destructive, in their need to consume everything. This ties into the motif of overindulgence, where trying to have it all leads to collapse. It’s a moment that feels both ambitious and tragic.

This part of the song makes me think about limits. As humans, we’re not built to take in everything all at once. The narrator seems to know this, but they push forward anyway, which makes this moment feel even more powerful.

“The pull, yes, the pull… let me in”

Here, the narrator feels the pull of something greater. Maybe it’s knowledge, maybe it’s God, maybe it’s ambition—but whatever it is, it’s pulling them upward. At the same time, the “cordage of suffocation” suggests that this pull is also trapping them. It’s both a promise and a threat. This duality reminds me of Rilke’s line from The Second Elegy: “Every angel is terrifying.” Rilke’s point is that striving for something divine or perfect can inspire us, but it can also destroy us.

This tension between desire and danger is what makes this section so interesting. The narrator wants to give in to the pull, but they also seem to know it could suffocate them. It’s like they’re caught between two forces—one that lifts them up and one that holds them down.

What I find fascinating here is how relatable this struggle is. We’ve all felt the pull of something we wanted, even when we knew it might not be good for us. This section captures that perfectly.

“I was an angel, though plummeting”

This line is full of mythological weight. The narrator compares themselves to a fallen angel, someone who was once divine but is now cast out. The imagery of “the stars are as beams shining through the wheel” gives this fall a cosmic scale, as if the narrator is caught in something much bigger than themselves. Rilke’s The Second Elegy also explores this idea of divine separation: “We, the wasteful ones, plunderers of what is divine.” Both the song and the poem capture the pain of being close to something greater but never fully part of it.

This moment feels like a turning point. The narrator acknowledges their fall, but they also seem to accept it. There’s a sense of loss here—not just of grace, but of connection to something larger.

What I find most striking about this section is how personal it feels. The fall isn’t just about being cast out—it’s about the narrator’s own choices and actions. It’s a reminder that separation often comes from within.

How I Connected The Dots

“Pulldrone” feels like a descent into chaos, but it’s also a cycle—one that begins and ends with the same haunting refrain: “I am nothing.” It’s a song about trying to grasp something bigger than yourself, whether it’s knowledge, God, or even just meaning, and being crushed under the weight of that pursuit. That’s a theme Ethel Cain has explored before, especially on Preacher’s Daughter, but here, she leans fully into abstraction.

The twelve steps in the song remind me of a dark, inverted liturgy, each stage pulling the narrator further from grace and deeper into despair. This mirrors the same tension Rainer Maria Rilke explores in The Second Elegy, when he writes, “Every angel is terrifying.” Cain’s narrator craves divine knowledge but finds only separation and emptiness. The result is a story of longing that becomes punishment.

The line “I will dislocate my jaw to fit it all in” perfectly captures this self-destruction. It’s not just about hunger for knowledge—it’s about excess, the idea of consuming more than you can handle, and that reminded me immediately of Anne Carson’s The Glass Essay. In that poem, Carson’s narrator talks about “desire doubled by knowledge” and the pain that comes with it.

Cain taps into this same truth: the pursuit of beauty, love, or understanding can overwhelm and break us. As the song moves through stages like assimilation, aggrandization, and resentment, you can feel that weight bearing down on the narrator. By the time we reach the lines “I want to know what God knows,” it’s clear this isn’t about transcendence anymore—it’s about collapse.

Even the structure of “Pulldrone” reflects the same cyclical struggles that Tomas Tranströmer explores in Tracks. The song starts in apathy and ends in desolation, but instead of feeling like progress, it loops back on itself. Tranströmer writes, “We grow still, we are led slowly forward,” capturing the idea that even as we strive for answers, we find ourselves returning to the same place. Cain does this with her ouroboros imagery and her repetition of “I am nothing,” showing that the search for meaning can become its own kind of trap.

What makes “Pulldrone” so devastating—and so effective—is how it blends the personal with the universal. Whether you read it as a critique of religious faith, a meditation on ambition, or a statement on the human condition, it hits hard because it’s so deeply tied to our own endless, messy attempts to make sense of the world.

The post Pulldrone Ethel Cain Meaning And Lyrics: What Ouroboros, Angels, and Apathy Have in Common appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.