Following the success of their debut release The Seven Stars and the Spring EP parts 1 and 2, Amsterdam’s Quazar released their first album, Seven Stars, on Go Bang! in 1991. Led by producer Gert van Veen and Eric Cycle, the album is a 14-track journey capturing the energy of Amsterdam’s vibrant house scene at the time.

The record, now remastered for 2024 by Marco Antonio Spaventi, still holds its edge, blending techno, rave, acid, tribal beats, and soulful house with spacey ambient moments. Tracks like The Future, with vocals from Surinamese singer Farida Merville, and Change for the Better highlight the duo’s ability to fuse vocal energy with instrumental grooves. Instrumentals like Cycledrops and the remix Dragonfighters have become enduring classics.

Quazar’s live energy is evident in tracks like Day-Glo, recorded at Amsterdam’s Paradiso during their Atmosphere tour with Jamaican reggae group Surkus. With themes of liberation running through the record, Seven Stars stands as a snapshot of house music’s early days and its spirit of freedom and experimentation.

With The Seven Stars recently re-released by Superstition Records, we dug into the creation of its iconic lead single, and how the album’s legacy has evolved, with Quazar’s Gert van Veen.

The creation of “The Seven Stars” seems to have been deeply influenced by a vivid dream. Can you tell us more about how dreams or subconscious experiences have shaped your creative process over the years?

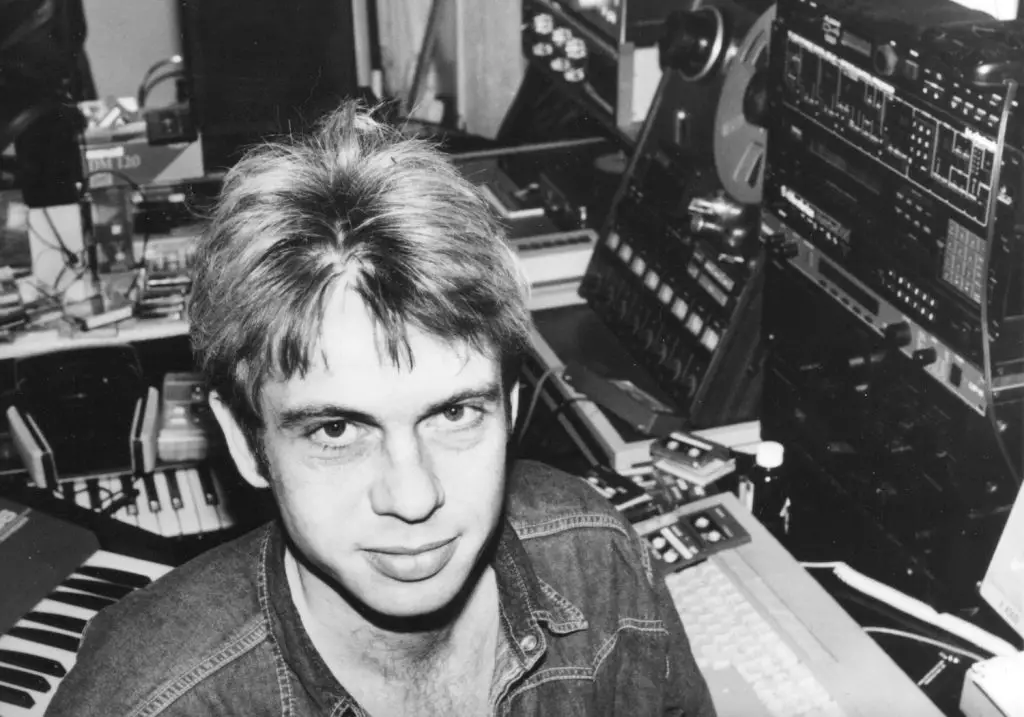

On a summer night in 1990, I was jamming in my home studio on my Korg 707 synthesizer when, out of nowhere, this penetrating riff flowed from my fingers. For the rest of the session, I kept working on the idea because it felt like something special. That night, I had a very vivid dream about a constellation of six stars, where suddenly a seventh star appeared. This was the sign for the seven tribes in the valley (that I was watching from a hilltop) to come together. It marked a new beginning.

The next morning, when I woke up, I realized there was a connection between the dream and the track I’d been working on. I decided to call it “The Seven Stars.”

I’ve been writing down my dreams all my life, as they sometimes help me understand my deeper feelings and subconscious mind.

How did the move from Utrecht to Amsterdam impact your music and career, especially during such a transformative period in your life in 1990?

I was born and raised in Utrecht, a beautiful, quiet medieval town. I lived in the old center near the Oudegracht (the Old Canal) in a cozy little house, so it took me quite some time to find the courage to leave. But I already had a job as a journalist for the Volkskrant newspaper in Amsterdam. More importantly, Amsterdam had Club RoXY with DJ Eddy de Clercq, the godfather of the Amsterdam house scene. From the summer of 1988, I was at the RoXY every weekend, completely hooked on the new dance music from Chicago, New York, and Detroit.

“The Seven Stars” had a significant global impact in the early 90s rave scene. What was it like to learn that your music was resonating across the world, particularly without the instant communication tools we have today?

It was incredible to realize that your music resonated across the world. For a small country like the Netherlands, it was always a big deal when ‘our’ rock bands achieved international success, like Shocking Blue with “Venus” in the 60s and Golden Earring with “Radar Love” in the 70s. This was front-page news. The UK and USA were dominant in the rock world, and small countries like the Netherlands weren’t seen as major players. That changed with the house revolution. The burgeoning house scene was much more liberated. Records could come from anywhere, not just the USA or UK.

There was an international network of import record shops and labels. Communication was via landline and fax machine. Our record company, Go Bang!, would hear from shops about which records were hot and selling. The shops had their own charts. I’ll never forget visiting one of the top house record shops in New York in the summer of 1990 and seeing a top 20 chart on the counter with another Go Bang! release of mine, “House of Venus.” I was silently glowing, haha.

The rerelease of “The Seven Stars EP” includes a remake of the original track. What elements did you aim to preserve, and what new aspects did you explore in this updated version?

The idea of rereleasing “The Seven Stars” has been floating around for quite some time. I asked many of my producer friends if they’d want to do a remix. Most of them didn’t dare to touch the original; they said they couldn’t improve it. I agree. So, I made a 2024 recreation of the original and asked my friend, renowned house producer Olav Basoski, to mix the track, hoping he could give it a slightly more modern feel. And he delivered.

The use of your earlier psychedelic experiments in “The Seven Stars” gave the track a unique color. How do you see the relationship between your early music and the techno/house sound you later developed with Quazar?

I’ve always been into 70s space music, from early Pink Floyd to Gong, Byrne & Eno, and more. My first bands made very experimental guitar music, or rather soundscapes, using effects from two Akai tape recorders for echo FX. I had hours of tape jams that were never released. In the late 80s, when affordable samplers became available, sampling became integral to house and hip hop. While others were sampling other people’s records, I thought, “Why not use my collection of personal music and unique sounds from those old tapes?”

House music was an empty canvas. The only certainty was a four-to-the-floor beat at 120+ bpm. For the rest, it was ‘anything goes.’ Using snippets of my old soundscapes proved effective, and I’ve kept using unexpected sounds and textures ever since.

You mentioned consulting the I Ching during the creation of “The Seven Stars.” How does spirituality or mysticism play a role in your creative process today?

Music, to me, is very spiritual, though it’s hard to put into words. Music is a language without words. The I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes, has been special to me for a long time. When I created “The Seven Stars,” I asked the I Ching what the track represented. The answer was hexagram 40, “Liberation.”

Liberation is what house music has always been about to me. Dance and let go of everything that bothers you—even if it’s just for a little while on the dance floor. That’s the essence of house music, captured in lyrics like “Release yourself” or “Set yourself free.”

The sampling of “The Seven Stars” by Rick Wilhite, which resurfaced in Moodymann’s set for GTA, brought your track back into the spotlight. How do you feel about this type of unsanctioned use of your music?

It depends, but mostly I feel honored. For instance, Rick Wilhite sampled the main theme of “The Seven Stars” and added a heavy kick. Seeing it used in Moodymann’s set for Grand Theft Auto amazed me. Still, it would have been nice if they had credited Quazar.

The B-side, “Day-glo,” was sampled often too. Faithless used almost all of it for their track “Sweep” but contacted me and paid for it, which was nice!

“Day-glo” was quite different from “The Seven Stars,” yet it gained significant attention as well. What was your reaction when Ricardo Villalobos and Faithless acknowledged the influence of “Day-glo” on their music?

“Day-glo” was indeed different. I needed a third track to finish the EP but couldn’t find anything that matched the other two tracks. The night before mastering, I started from scratch and created “Day-glo” in one session. I was drained from loud, banging music and needed something lighter. When I finished, the first daylight shone through my studio window, so I named it “Day-glo.”

I’m still proud of it, though it feels like it fell into my lap. Years later, DJs like Ricardo Villalobos would come up to me and say how much they loved it. When I met Ricardo in 2005, he hugged me and said, “Thank you for ‘Day-glo’!” That meant a lot.

The underground success of “The Seven Stars” in the early 90s spread through word-of-mouth and physical releases. How do you think the way music spreads today, with the internet and streaming, would have influenced the trajectory of Quazar back then?

Everything moves faster now. It’s easier to reach the world instantly. In 1990, there wasn’t much promotion for “The Seven Stars,” but DJs discovered it in record shops and found it worked in clubs. It resonated with the booming rave generation in the UK, Australia, the USA, and newly reunited Germany. I only learned about its success after it became an international hit.

In the 90s, Amsterdam was a hub for the early house and techno scene. How has the electronic music landscape in the city evolved since then, and what differences do you notice in how new generations approach music production and live performance?

After the 90s, there were some quieter years, but around 2005 things picked up with a new generation and legendary clubs like Trouw and Studio 80. Festivals have become more important, with many in the Amsterdam area. Amsterdam Dance Event 2024 hosted around 1,000 parties, attracting half a million visitors.

I’m not a fan of how social media dominates artist promotion now, but it’s the reality. Many of us from the 90s still long for the anonymity and energy of early raves, where you could truly let go. Some clubs now ban phone cameras to recapture that spirit. Dance music is bigger and more commercial than ever, but the international underground remains vibrant

The Seven Stars is out now on Superstition Records: https://superstitionrecords.lnk.to/SevenStars

The post Magnetic interview: Quazar and The History of The Seven Stars appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.